What is it about the tongue, this otherwise negligible digestive organ that slips into and out of meaning whenever it damn pleases, that frequently haunts and mobilizes the minoritarian subject? How do we begin to contend with and engage the profusion of tropes and metaphors referring to this curious thing of abjection—a moisty, slimy thing, no less—that pervade the diasporic experience? While the colonial-bourgeois novel ruminated on and centered the duality of Nature and consciousness since the dawn of primitive accumulation and capitalist profiteering, colonized peoples sought refuge in, and pushed against, the tongue, without doubt for its faculty to contain and intone language, i.e. that which, per Mirene Arsanios, “can turn against me at any moment and deprive me of my words.”[1]Language, building on Frantz Fanon’s sociogenic principle, is a death trap par excellence; it separates grievable lives from expendable ones, and marks as other, as threatening, that which appears innate to entire subjugated communities and populations. And so, if the organic carrier of language—the tongue, that is—has and continues to betray us amid situations where concealment is tied to survival, do we account for it as a foreign body occupying our own and, as a result, do we simply cut it off?

Instead, and as a seemingly counterintuitive impulse, poète maudit Justin Chin, in his quixotic pursuit of belonging in 1990s AmeriKKKa, and as a seemingly counterintuitive impulse, demanded to have that foreign body penetrate him—in other words, to have his butt, that solar orifice that can only be his own, licked—and to summon a form of reception whereby a tongue-in-action does not assist violence, but instead gestures towards a field of potentiality: “Hey — my butt had ever reason to be careful / it knows where it’s been; / it’s had enough of this bigotry / & poverty & violence [...] / so when that first slobber, smack, / slurp found its way into that / crack & up that uptight little asshole / it was like the Gay Pride Parade, / the Ice Capades, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade / and Christmas happening all at once.”[2]

Artist Tarek Lakhrissi (b. 1992, Châtellerault, France) is no stranger to the ravages of the tongue, and to the uncharted territories language can force him into. Though more recently organized around materiality and sculptural output, his artistic practice, which spans several mediums—video, installation, and text—and takes on diverse articulations, is largely informed by fictional and literary devices, and concerns itself with our often unconscious, but also premeditated, deployment of words and signs. These meaning-making tools, for Lakhrissi, allow him, and audiences experiencing his work, to excavate forgotten histories of violence and bear witness to unresolved colonial injustices. And yet, because his practice roots itself in, and is structured around, decolonial, queer, and feminist praxes and methodologies, his work doesn’t suffice itself with making legible history-with-a-capital-H’s otherwise hidden stratas, or questioning existing structures and systems that distribute precarities; rather, it actively creates room, and designs stages, for racialized and queer(ed) communities to rehearse alternative futures and practice world-building, opening up counter-spaces for expressions of alterity and communitarian belonging to circulate and prosper away from the watchful gaze of the state and its repressive apparatuses.

As part of his newly conceived installation at the Kunstverein Kevin Space, I wear my wounds on my tongue, Lakhrissi accounts for and invites contingency and mutuality, drawing the contours of his proposition in relation to the communities it aims to speak to. Taking cue from Chin’s reluctant, yet plucky, (corporeal) titillation with, and (psychic) capitulation to, the tongue, the artist produced five resin sculptures, each a different color, that embody the shape of, and borrow texture from, the ill-famed digestive organ, which Lakhrissi likened, in a conversation we had over WhatsApp, to jellyfish, those gooey oceanic species that brush against you and release painful stingers when they care and desire, as any loving stranger with a Mars in Scorpio would. These sculptures, when hung around the exhibition space, conjure indeterminacy. When looked at from a given angle, they may be brushed off as props used to convey alien form in a low-budget science-fiction film; but when approached from an elsewhere, or even an otherwise, they can appear as weapons—sharp, imposing, and lethal as weapons are meant to be and present themselves as—ready to be toyed with, utilized, made love to, or feared. The sculptures are reminiscent of, and perhaps thought of as a continuation to, similar installations by Lakhrissi, Perfume of Traitors (2020) and Unfinished Sentence II (2019), presented respectively at VITRINE in London, CRAC Alsace, and the Palais de Tokyo, consisting in distorted metal blades and spears that point, ever so threateningly, towards audiences, but are manufactured so as to be rendered harmless.

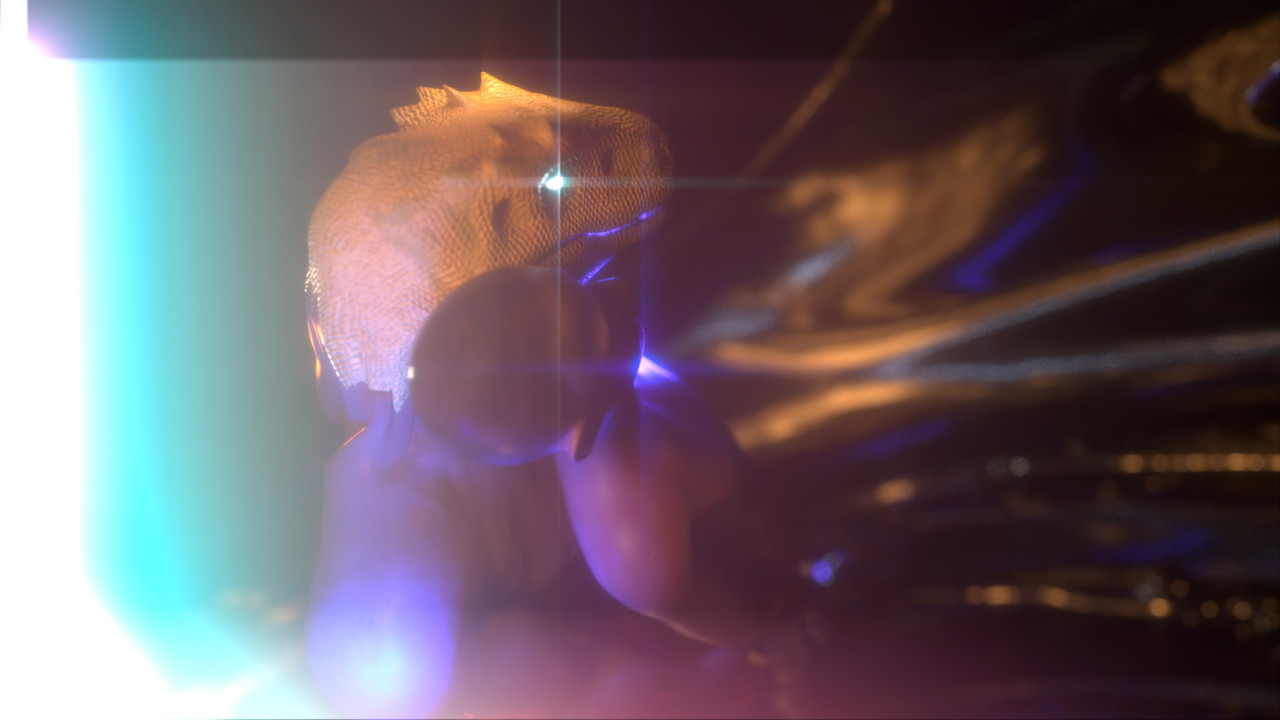

Two video works are also on show through I wear my wounds on my tongue: in Hard to Love (2017), which premiered as part of the 13th Baltic Triennial, a hand is seen repeatedly—and frustratingly—holding a glass of water and returning it to the table, as an ominous voice comes out with a series of sentences that start with “I didn’t learn how to -”; on the other hand, The Art of Losing (Love Scene), a one-minute extract from an as yet unfinished film, stages a languorous and sultry sexual encounter between an Arab fugitive and a part human, part dinosaur go-go dancer. And while the former speaks of tongues that fail to make legible, and the violence that agrips a minoritarian subject whenever they’re asked to make sense, the latter is a zany and kitsch exploration of what it means to surrender to, and derive pleasure from, the loving embrace of queer bodies and presences. Through those works, and the installation writ large, Lakhrissi shares more than just kinship with Chin—rather, it’s a common purpose he is after, that of wanting to summon an act of reception through tongues that intimate blissful unknowns, and of giving aspiration that, in the words of Puff Daddy in Blood Orange’s “Hope”, “maybe one day I’ll get over my fears and I’ll receive.”

Text by Edwin Nasr

[1] Mirene Arsanios, Notes on Mother Tongues (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020)

[2] Justin Chin, “Lick My Butt” in Bite Hard (Manic D Press, 1997)

Tarek Lakhrissi (b. 1992, Châtellerault, FR) is a visual artist and a poet based between Paris and Brussels. He currently teaches at CCC Research Master Program of the Visual Arts Department at HEAD (Geneva School of Art and Design). Lakhrissi has recently been exhibited internationally, amongst others, at Haus der Kunst, Munich (upcoming), MOSTYN, Wales (2021), Museum of Contemporary Art; Biennale of Sydney, Wiels; Bruxelles, Palais de Tokyo; Paris, Palazzo Re Raubengo/Sandretto, Guarene/Torino (all 2020), Hayward Gallery; London, Auto Italia South East; London, Fondation Lafayette Anticipations; Paris (all 2019). He is nominated for the 22nd Fondation Pernod Ricard Prize (2020-2021).

☞ Open Reading Group: Bite Hard by Justin Chin

Tuesday, Sept 28, 7–9pm

For registration or more information please send us an email at office@kevinspace.org