In the modern image of the individual body, sexual life, eating, drinking, and defecation have radically changed their meaning: they have been transferred to the private and psychological level where their connotation becomes narrow and specific, torn away from the direct relation to the life of society and to the cosmic whole. In this new connotation they can no longer carry on their former philosophical functions.

(Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and his world, 1965)

In ‘Rabelais and his world’, Bakhtin discusses the idea of the ‘Grotesque’, a collectivist idea of medieval life where the body itself was of the public domain, and group feasting, public defecation, urination and sex characterised an open and porous social body. He discusses the psychological changes that occurred when people became removed from the direct fruits of their labour, with their own produce sold back to them by the ruling classes at inflated prices, and when the church restructured the social body around the family unit, around the production of new bodies. This abstraction in turn created psychological abstraction, with the body becoming individuated, removed from its social mass, and privatised. In this way the excesses of the open porous social body were to disappear or become codified and closeted into carnivals or other similar feast days. The ‘Grotesque’ is summed up in the image of a gaping open mouth, the idea of consuming the world through absorption into the body. Metaphors of incorporation emerge from the physics of the body and its relationship to the world, and in this show the body’s physicality is compared to its economic value.

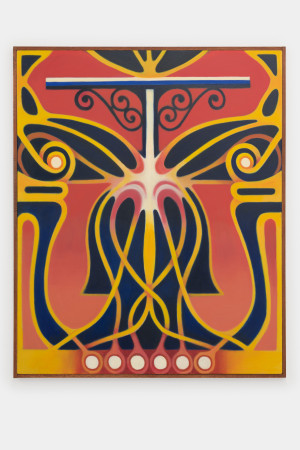

The exhibition presents us with three paintings depicting a table, the site of incorporation. One of them shows a construction worker imagined as part of an anatomical diagram, a filtration system which begins to turn into almost text like forms. Two ‘tabletop’ paintings show two figures at a cafe intertwining and abstracting into Art Nouveau-like ornament. Ornament is what is decorative, or non-essential to an object. Here ornament is related to excess, to idle chat, sexual frisson. The sculptures also refer to the table and to excess: here Thomas Aquinas has been incarnated as four Art Nouveau table legs attached to sweeping brushes and dustpans. Aquinas catalogued a taxonomy of sexual sins and these sculptures are allegorical depictions of the sins of wastefulness: Coitus Interruptus, Self Love and Sodomy - spilled seed needing to be swept up.

Non-normative and non ‘productive’ sex acts are one of the ways the church attempted to structure sexuality solely around the production of subsequent generations of workers. Our attitudes towards sexuality in general were thus formed under social and economic principles which have been internalised into our bodies as shame and guilt. Sexual feeling and pleasure have been pathologised. Fitzpatrick in this show suggests that the physics of our bodies are metonymic models for social structure and as these structures abstracted over time into forms of religion and state control, they subsequently restructured and alienated ourselves from our own bodies.

Justin Fitzpatrick, born in 1985 in Dublin, lives and works in London and Brussels. Recent solo exhibitions include F-R-O-N-T-I-S-P-I-E-C-E (Seventeen, London) and Uranus (Sultana, Paris). His works have been shown in the following group exhibitions: Whisky et Tabou, Musée Estrine, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (2017); Amazing girls / It’s complicated, Kevin Space, Vienna, (2017); Streams of Warm Impermanence, DRAF, London (2016); Animal Mundi, Barbican Arts Trust, London (2016); Life is On, Jakob Kroon Galerie, Stockholm (2016); Caput Medusae, Westminster Waste, London (2016); I would have done everything for you…Gimme more!, London (2016); Bloomberg New Contemporaries, ICA, London (2015).